Costs, Benefits, and Risks, Oh My! Navigating Tradeoffs

Failing to balance tradeoffs effectively can result in decisions we regret.

A previous version of this post was published on Psychology Today.

We make countless daily decisions, ranging from more automatic ones like getting out of bed when the alarm goes off to more effortful ones like making the decision to buy a new house. Most of these decisions depend on how we assess costs, benefits, and risks. Before we dive in, it's important to clarify how our perceptions and our consideration of short- and long-term consequences shape our decisions.

First, there’s a difference between actual costs, benefits, and risks and how we perceive them. In most situations, objective standards matter less than our subjective perception. For example, while a new appliance has an objective cost (i.e., its price), whether that cost seems reasonable, too high, or too low, is ultimately subjective. This subjectivity opens the door for cognitive biases, such as loss aversion, anchoring, or negativity bias, to influence how we approach decisions.

Second, short- and long-term costs, benefits, and risks often differ significantly. For example, buying a house often requires different short-term costs (e.g., closing costs, time and energy to house hunt) than long-term costs (e.g., mortgage, taxes, utilities, maintenance, time and energy to clean). We often base our decisions on short-term perceptions, which can lead us to overlook long-term implications and face unintended consequences.

With these distinctions clarified, we can better understand how costs, benefits, and risks shape our decisions.

Costs

Costs are the resources a specific choice demands, such as time, energy, or money. For example, going to the grocery store requires time, energy, and transportation costs. There’s also the time and energy required to put together a shopping list. The items we choose may reflect both short-term financial costs and the longer-term costs of time and energy needed to prepare specific meals.

An act as simple as grocery shopping involves multiple cost considerations, and the extent to which we consider these costs depends on the situation. For example, we may assess the financial costs of various items differently if it’s been a tight month financially than if it hasn’t. Additionally, we might be more conscious of time and energy costs when planning meals during a busy week.

Costs generally do not exist in a vacuum, though. In most cases, we evaluate them relative to the benefits we foresee.

Benefits

Benefits are the rewards or positive outcomes we gain from our decisions. For example, when we go to the grocery store, we benefit not only by obtaining nutritious food but also by enjoying what we eat.

Benefits may be short term or long term. Sometimes we forego a short-term benefit to gain a greater long-term one, such as making an investment. Other times, we prioritize short-term benefits, such as splurging on a meal at an expensive restaurant, even if it means having less money to spend the rest of the month1.

Benefits seldom exist in the absence of costs, even if those costs are minimal. For many decisions, we assume that incurring the costs will lead to the expected benefit, making the decision a straightforward balance of costs and benefits. Few decisions, though, are guaranteed to bring about the expected benefit, which means we must also consider risk.

Risks

Risk exists when the probability that our efforts will lead to the expected benefit is less than 100% or when there is some probability of an unexpected negative outcome. For example, when we go to the grocery store, we expect the costs we incur will lead to benefits. However, there’s a small risk that something bad will happen, like having a car accident. Although the probability is very low, it means the outcome isn’t guaranteed2.

Before the pandemic in 2020, most people didn’t consciously evaluate the risk of grocery shopping. Once COVID became a salient risk, many people thought more consciously about it3. Over time, as the risk became less salient, people's concerns about the risks of grocery shopping waned.

New risks, recent negative experiences, and traumatic events can make certain risks more salient, leading us to deliberate more and often overestimate their probability. This overestimation may cause us to take extreme measures to minimize risks, resulting in a form of loss aversion. Once these risks become less salient, they fade into the background, and we may automatize risk-reducing behaviors4, such as by putting on a seat belt. Conversely, we might act as if the risk is minimal, becoming careless simply because nothing bad has happened before.

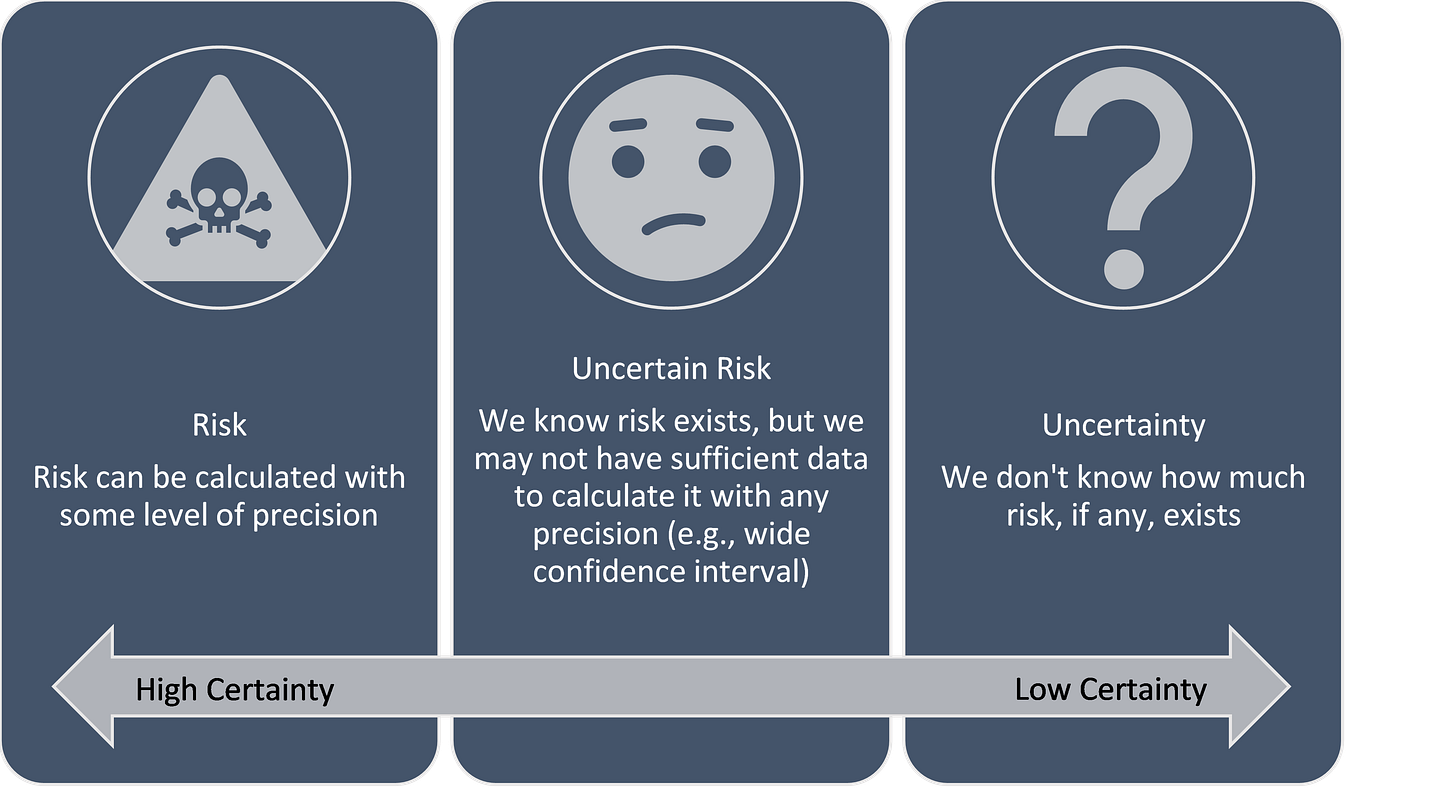

It’s also important to differentiate risk from uncertainty, which I do in Figure 1. To illustrate, starting a new business involves risks that are influenced by the current state of the economy. While some risks are known, we cannot predict whether they will change in the future, which creates uncertainty. The farther into the future we try to foresee, the more difficult it is for us to account for objective risk.

Risk introduces complexity into decision-making. Clear risk probabilities are often hard to calculate, and even when they are, they may not capture all the factors that influence actual risk in a given situation5. As a result, we make tradeoffs between costs and benefits, which are influenced by our perception of the risks involved.

The Complicated Nature of Tradeoffs

Most decisions boil down to assessing whether the costs justify the likely benefits. Are the costs worth the probability of receiving the expected benefits, considering both short- and long-term outcomes6 and the associated risks?

It’s important to note that we don’t necessarily rely on complex mathematical reasoning, nor do we necessarily make what would be evaluated as the best choice using such reasoning. Instead, as Herbert Simon argued, we tend to use a “good enough” standard, what he referred to as satisficing7.

For decisions we make unconsciously, we often don't consider salient risks. We just assume that if we expend the resources to do something, we'll receive a benefit. If we do consider risks, we may develop automatized behaviors designed to reduce those risks, such as washing our hands after handling raw meat or locking our doors when we exit our vehicle. These assumptions, with or without risk adjustments, become part of the heuristics we use to guide our behavior.

For more conscious decisions or in less routine environments, we may rely on both existing heuristics and situation-specific information. For example, most drivers develop heuristic rules for driving that they unconsciously apply in familiar situations, but they may adjust them more consciously when the situation calls for it8. Thus, while we may have some heuristics that generally govern our behavior, situation-specific factors often affect the salience of, and weight we assign to, existing heuristic-driven cost, benefit, or risk perceptions. This explains why we make drastically different choices in some situations than in others, even if the situations are comparable. Small, but salient, situational differences can cause heuristic adjustment, leading to different decisions. Ultimately, the quality of our decisions depends on how well our heuristic-driven assessments align with reality.

Footnotes

Many of these cases involve tradeoffs we make, as I discuss below. And this would be a case where choosing to do so could come with one of those unintended consequences if some additional opportunity or financial demand crops up.

It may be so low we don’t even consider it to be a salient risk.

We may not know exactly what that risk is, but we certainly know there is some level of risk. Whether or not that leads to changes in people’s behavior likely concerns how high they perceive that risk to be.

Sometimes, though, our attempts at risk reduction may not have their intended effects, such as in the case of parents opting out of vaccinating their children.

For example, the probability of dying in a car accident is 1 in 114. Yet, in any given situation that probability is likely higher or lower depending on a variety of factors (such as driver competence, driver BAC level, road conditions, time of day, driver fatigue).

Focusing only on short-term benefits may increase the risk of long-term negative consequences.

It represents a combination of satisfy and suffice. Hence, a satisficing decision could be considered one that is sufficiently satisfactory.