Emotions: The Hidden Drivers of Decision Making

Emotions play a role every choice we make—for better or worse.

A previous version of this post was published on Psychology Today.

To date, I’ve written a fair amount about human decision making on this site. However, one topic has been more of a supporting character than a lead: the role of emotion in decision making. While implicit in many of the writings I’ve shared, emotion itself seldom gets the explicit attention it deserves. My aim here is to change that.

Emotion often receives short shrift in discussions of decision making. Dual-process researchers typically assign emotions to the intuitive, fast-acting System 1, contrasting them with the supposedly more rational and deliberate decisions resulting from System 2. This framing reinforces a simplistic narrative: that emotions are obstacles to sound decision making, liabilities to be managed or set aside in favor of cool, analytical reasoning—especially in high-stakes scenarios. However, as I’ve argued previously, human decision making rarely fits neatly into a dual-process framework, and this oversimplification does a disservice to the complexity of the processes involved.

In reality, emotions are far more complex and integral to decision making than the simplistic dual-process perspective suggests. They are neither inherently good nor bad but instead wield the power to both enhance and hinder our choices. To unpack this complexity, we must first consider what emotions are and how they shape the decisions we make.

Those Pesky Emotions

We experience emotion due to “a personally significant matter or event” with “the specific…emotion (e.g., fear, shame) [determined] by the specific significance of the event.”1 In other words, emotions don’t arise randomly—they are reactions to events that matter to us. The meaning we attach to those events often determines which emotion we experience and how intensely we experience it.

While entire books could (and have) been written on the nature of emotions, four key aspects are particularly relevant to their role in decision making:

Emotions are often explicitly tied to desired and feared outcomes, reflecting a strong connection to our values and goals.

Emotions can arise both in anticipation of and in reaction to experiences.

Emotions often produce a corresponding action tendency, serving as a source of motivation.

The stronger the emotion, the greater its influence on our decisions.

These elements provide a foundation for understanding why emotions are such a critical—and often misunderstood—component of decision making. Understanding them also sheds light on why emotions can both enhance and undermine decision making.

Emotions and Goals

As I’ve written previously, our goals and values play a central role in decision making, shaping what we prioritize, how we evaluate options, and ultimately the choices we make. Our emotions are often inextricably linked to those goals and values (Blanchette & Richards, 2012; Carver & Scheier, 2019; Lerner et al., 2015).

For example, fear may arise when we perceive a threat to a deeply held value, such as personal safety, while joy may emerge when we experience progress toward an important goal, like achieving a long-sought professional milestone. These emotional reactions directly tie to the goals and values we hold, providing relevant information about how we interpret and respond to the world around us. And so, while there are some situations that will produce similar emotions regardless of who experiences them, in many other situations, the experience of emotion is shaped by our frame of reference—which ultimately includes our goals and values.

This perspective isn’t new. Herbert Simon (1983) argued that “to have anything like a complete theory of human rationality, we have to understand what role emotion plays in it.” Centuries earlier, David Hume articulated a similar view in his first major work of philosophy, A Treatise of Human Nature (1739–1740). In the second book, Of the Passions, Hume famously declared that “reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.” Hume’s declaration underscores Simon’s argument, centuries later, that emotion is integral to human rationality. Both highlight that reason, far from being autonomous, depends on emotion.

And in his book, Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain, Antonio Damasio went even further, asserting that emotion is not just important to decision making—without it, we wouldn’t be able to make most decisions. His work demonstrated that individuals with brain damage that impairs their emotional processing often struggle to make even simple decisions, despite retaining their cognitive abilities. This suggests that without emotions, we would lack the ability to evaluate our preferences for one choice over another.

Thus, far from being a bug in the system, emotions are a feature of the human decision-making process. They help us navigate the complexity of value-laden decisions by signaling which options align with or deviate from our goals and values. This signaling function is what makes emotions indispensable, particularly in real-world decisions where ambiguity and complexity dominate. While emotions can sometimes complicate our choices, they are ultimately what give decisions their meaning and direction.

Anticipatory vs. Reactive Emotions

We experience emotions both in anticipation of an event and in reaction to events that have already occurred (e.g., relief, joy). Anticipatory emotions, such as fear or excitement, are rooted in the uncertainty of the future (Baumgartner et al., 2008). When we anticipate positive outcomes—like attending a sporting event we’re looking forward to—we may feel excitement or enthusiasm about what’s to come. Conversely, when the uncertain future carries negative implications for us—such as realizing we’ve misplaced our car keys—we might experience fear or anxiety over what could happen if we can’t find them.

Reactive emotions, in contrast, arise after the event has transpired. The excitement we feel about a sporting event can transform into elation or joy if our team wins the game, or into sadness and irritation if our team loses. Similarly, the anxiety we feel about losing our car keys may turn into relief once we find them—or escalate into frustration or anger if we don’t.

Both anticipatory and reactive emotions are deeply tied to the goals and values we hold, as these determine the significance we assign to the event. For instance, a highly competitive sports fan might experience greater elation or disappointment than a casual observer, depending on the outcome of the game. The implications of these emotions for decision making often stem from the action tendencies they produce.

Emotions Produce an Action Tendency

Both anticipatory and reactive emotions produce action tendencies corresponding to those emotions. These action tendencies shape how we respond to the situations that evoke them. Anticipatory positive emotions, such as excitement, create motivation to actively engage with the future event that elicited the emotion. Conversely, anticipatory negative emotions, such as fear or anxiety, often motivate us to eliminate or avoid a potential aversive state or to limit the damage that aversive future state may cause.

Reactive emotions, by contrast, produce action tendencies in response to events that have already occurred. Positive reactive emotions, such as joy, tend to motivate behaviors aimed at maintaining or amplifying the emotional state, such as by engaging in additional enjoyable activities or seeking reinforcement of the positive emotion from others. Negative reactive emotions typically push us to reduce discomfort, either through avoidance behaviors—like withdrawing from aversive situations or taking fewer risks—or by seeking relief through distraction or pleasure-seeking activities2.

In both cases, the valence of the emotion—whether positive or negative—colors our perceptions, appraisals, and attributions. Positive emotions create a stronger positivity bias in decision making, where we might underestimate risks or overvalue expected gains. Negative emotions, however, infuse a stronger negativity bias, often making us more risk-averse as we overestimate potential risks or undervalue possible gains. These biases, while often adaptive, can skew our decision-making processes depending on the context and intensity of the emotion.

Stronger Emotions are More Impactful

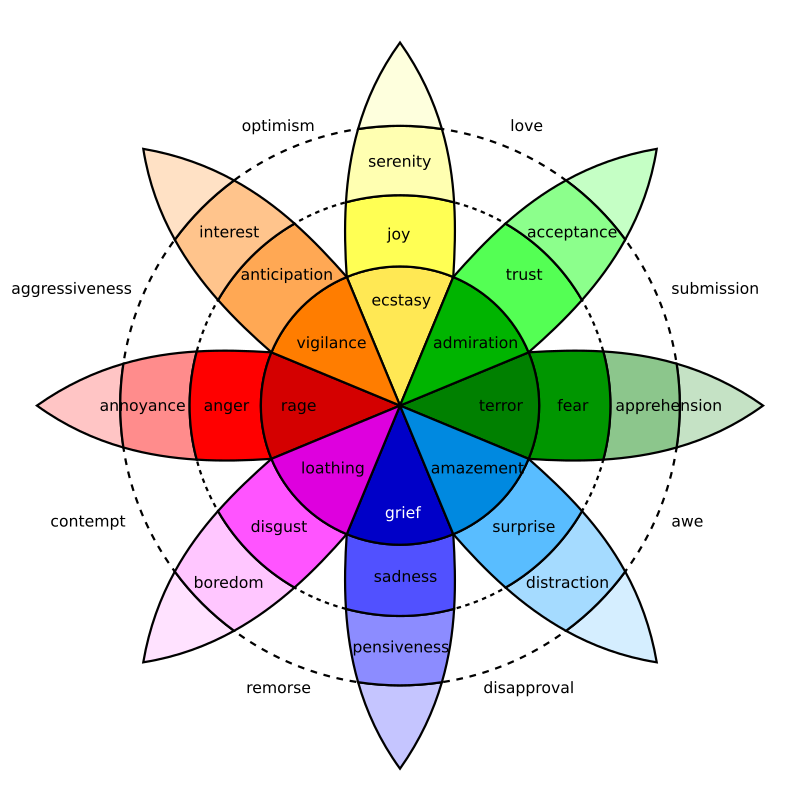

Thus far, the concept of positive and negative emotions has been discussed at a broad level. However, emotions also vary significantly in intensity, which influences their impact on decision making. Robert Plutchik’s Emotion Wheel (see Figure 1) offers a useful framework for understanding this variation3. For example, fear might manifest as mild apprehension at lower levels of intensity, but escalate to terror at higher levels. The more significant or impactful the experience, the greater the likely intensity of the emotion.

The intensity of an emotion is often shaped by the psychological context within which it occurs. Familiar situations tend to evoke less intense emotional reactions than novel ones, as we’re better equipped to manage familiar scenarios. Similarly, when a situation aligns closely with something we deeply value—or threatens an important goal—the resulting emotional response tends to be more intense.

Emotional intensity (whether positive or negative) is likely to influence how much sway the emotion will have over decision making. Stronger emotions are more likely to override competing motivational goals and drive behavior that aligns with the emotion itself. For example, a state of rage is far more likely to dominate our judgment and actions than mild annoyance, and a state of amazement will exert greater influence than mild surprise.

Intense emotions can even bias our perception of a situation, amplifying certain aspects while diminishing others. For instance, rage may lead us to see neutral actions as hostile, while amazement might cause us to overestimate the significance of an event.

More intense emotions not only make it harder to act against their associated action tendencies, but they also consume a significant portion of our cognitive resources. Because our capacity to process information is limited, stronger emotions can leave fewer resources available for evaluating other decision-relevant information. This cognitive load, coupled with biased perceptions, makes it more challenging to consider alternative perspectives or weigh the full range of potential outcomes.

Emotions Are Both a Boon and a Bane for Decision Making

Although it’s common to see arguments that we should seek to remove emotion from our decision making, the reality is that we can’t. Even if we could, we wouldn’t want to—because without emotions, we wouldn’t be able to make decisions very well at all. That may seem counterintuitive, but emotions are play a role in discerning the value of different decision options. They help provide the context and meaning that allow us to evaluate choices and prioritize what matters most.

Damasio’s research gave rise to his influential somatic marker hypothesis, which posits that our emotional processes play a crucial role in guiding decision making. According to this hypothesis, our brains connect physiological signals to the emotions we experience, using this information to guide us toward or away from certain options. These signals, or "somatic markers," serve as cues for the brain to use to help us narrow down the overwhelming array of possibilities we might face. Rather than evaluating every option in detail, our emotions act as filters, focusing our attention on the most relevant alternatives. For individuals with impaired emotional processing, such as those with frontal lobe damage, this filtering mechanism is disrupted. Without these emotional cues, even simple decisions can feel paralyzing, as all options seem equally weighted.

While some decisions have a clear, correct answer (e.g., solving a logic problem or crossword puzzle), the majority of decisions we face are value-laden, requiring us to weigh subjective tradeoffs. For example, how would you know, without emotions, that earning a hundred dollars is better than earning five dollars or that two slaps in the face are more painful than one? These judgments may feel automatic, but they depend on the emotional systems that signal the relative significance of each option. Emotions, then, are not obstacles to decision making—they are the framework that allows us to navigate complex, subjective choices.

However, this strength can also become a liability. Emotions may help us assign value, but powerful emotions can also override other important pieces of information, narrowing our focus and leading to biased or impulsive decisions. As emotions become more intense, they often act as a strong driver of motivated reasoning, pushing us to interpret information in ways that align with the emotion rather than the broader context. For example, anger might cause us to disproportionately blame others for an unfavorable outcome, while joy might lead us to ignore potential risks. In these moments, emotions become a bane for decision making, biasing our judgments and undermining our ability to make balanced, well-informed choices.

Ultimately, emotions are neither inherently good nor inherently bad—they merely serve as a source of information and influence. Whether they enhance or hinder decision making depends on how well they align with the demands of the situation. Understanding their dual nature allows us to harness their benefits while mitigating their drawbacks. By recognizing the role emotions play in shaping our decisions, we can better navigate the complex, value-driven choices that define our lives.

There are times where we seek to maintain a negative emotion, but those tend to occur a lot less often. For instance, an individual might continue to dwell on feelings of anger toward someone who betrayed their trust, not because they enjoy the emotion itself, but because it reinforces their sense of justice or motivates them to take action (e.g., pursuing accountability or preventing similar situations in the future). This deliberate engagement with a negative emotion often serves a purpose, such as protecting one's values or maintaining a sense of control, even if it isn’t pleasant.

Evidence for some of the specifics of the wheel itself is lacking, but it’s still a good visual to demonstrate the way more intense emotions become more impactful.

I'm glad to see this post Matt, and thank you for putting it up. Specific comments follow -- a mixture of reactions, reflections and quibbles. I realise that this work is already published. Any value in such commentary then may be in contribution to your further reflection and discussion, and I hope that some of it may be useful in that role.

> In reality, emotions are far more complex and integral to decision making than the simplistic dual-process perspective suggests.

I strongly agree. But the reasons our narratives of psychology have favoured reasons over reactions have a lot to do with the size and complexity of the societies producing the psychology, and their own economic histories. As you likely already know, these rational-dominant narratives don't operate in all cultures, and so far as I've seen, are nigh impossible to find in pre-agricultural societies. There are whole sections of our own society who don't experience their minds in this way and are baffled when it's unpacked in this form. We're still dealing with the legacy of our history here.

> emotions don’t arise randomly—they are reactions to events that matter to us.

Not always true. Our emotional response is a synthesis of *everything* that's happening, including conditions not tied to a single event. Consider for example, the impact on mood of the state of our gut flora, the impact of immunocompromise on sense of wellbeing, or what happens to endurance athletes over the course of a long period of training. Then there's what happens in a range of psychopathologies where it's hard to tell whether a delusion creates the emotional reaction, or the emotion engenders the delusion. We could equally wonder what's happening in infant and early childhood development too, when emotional reactions are strong, but cognition is still developing.

Emotions can be reactive but the ontological tendency to pigeonhole them this way is a product of a rational-dominant society of contracts and agreements. (I know you're making a similar point, but my point is that it's not just legacy philosophy of mind, but legacy language of mind causing problems here.)

> Emotions are explicitly tied to desired and feared outcomes, reflecting a strong connection to our values and goals.

Not always true. Infants can display a fear of falling while having no idea what's happening. We are wired for emotional responses to some perceptions, regardless of our understanding of incident or apprehension of outcome.

> Emotions can arise both in anticipation of and in reaction to experiences.

And conditions, whether or not we entirely apprehend them -- please see my earlier points.

> Emotions often produce a corresponding action tendency, serving as a source of motivation.

Agreed, but behaviouralism struggles with mechanism here. It's one of the few times when I think it's the wrong framework to use.

> The stronger the emotion, the greater its influence on our decisions.

Rather, on 'responses' -- there may or may not be decisions attached.

> Our emotions are inextricably linked to those goals and values

Even more than that, we have whole human endeavours -- some expensive and risky -- designed principally to produce emotional effect. That's not just art, but crafts, sports, recreations and a range of human interaction styles. We're a social species that cooperates for protection, food-gathering and child-rearing while competing for sex and food, and our emotional responses are all geared around these evolutionary forces. Primatology tells us that we had prelingual signals with emotional effect long before we had complex language to link emotion with consequence. Anthropology shows that we retain and still use these facilities. Not all of this is goal-driven because we may have no conception of what we actually want, and yet feel compelled to act anyway.

> emotions are essential for discerning the value of different decision options

No they aren't, because we have automated decision-systems that can discern value. While popular among philosophers, this argument conflates the innate capacity of emotions to synthesise with the need for all synthesis to be emotional.

It's also a bit of is-ought fallacy: 'emotions are always involved, therefore they're always needed'. A more constructive point is that they're always involved, and therefore unwise to ignore.

> Emotions may help us assign value, but powerful emotions can also override other important pieces of information, narrowing our focus and leading to biased or impulsive decisions.

Yes, but further: emotions are typically short-term, self-focused, tribal syntheses while many of our modern social decisions require us to think in transpersonal terms. The prevalence of careerism, cronyism, factionalism, transactionalism and short-termism in policy selection and design tells us that we struggle with this. (In fact when I try to discuss transpersonal motives with most people, I get blank looks from some, while others think I'm talking metaphysics.)

> While emotions can sometimes complicate our choices, they are ultimately what give decisions their meaning and direction.

No -- they're only *part* of what nourishes our sense of meaning and direction. While it's hard to spontaneously pursue directions contrary to emotional reaction, it's also trainable, and whole cadres of people do it all the time. However 'meaning' and 'direction' might be recognised, they're not purely emotional in all people.

> Ultimately, emotions are neither inherently good nor inherently bad—they are tools.

I disagree. They're only tools in persuasion, entertainment and propaganda. Both experientially and behaviourally they're information, conditions and pressures -- part resource, part constraint. Our tools are therefore methods and techniques for understanding, exploiting, transforming and managing them.

This stuff is tricky yet critical. I love that you're presenting it and look forward to reading more.