From Balance to Allocation

How a simple shift in thinking can help you make better work-life decisions

A shorter and earlier version of this post was published on Psychology Today.

You can also hear AI Matt’s summary of the piece below.

If you search for “work-life balance” on Google—quotes included to keep things tidy—you’ll find that there’s a bajillion articles, frameworks, and thought-leader TED talks all trying to help you achieve balance. Technically, it’s only about 70.6 million hits, at least as of when I drafted this post1.

But the emphasis on achieving balance is part of the problem. You see, a lot of authors treat work-life balance like it’s a destination—some ideal mix of priorities you can lock in if you just download the right app, say no to enough meetings, or time-block your calendar relentlessly.

That version of balance, though—the one where we finally conquer the conflict between our work and non-work life—is a myth. It’s not something you get once and keep. It’s not a place you arrive at and then never leave. It’s something you manage. And the better frame for managing it isn’t “balance” at all. It’s personal resource allocation: figuring out where your limited pool of personal resources is going and managing it as well as you can so it actually works for your life.

There’s no magic bullet, no secret formula, and no clear roadmap for how to do it. In fact, for most people who feel as though they’re doing it reasonably well, they’ve often stumbled their way into it2. The purpose of my post here is to offer a better way of thinking about this issue—one that’s less about chasing balance as a goal and more about being a little more deliberate about how we allocate our limited resources. And who knows—maybe you’ll end up stumbling just a little less because of it.

Understanding Work-Life Balance

So what exactly is work-life balance? For a term that shows up a lot online—and that is allegedly more important than pay when looking for a job (Partridge, 2025)3—you'd think we'd have a shared definition by now.

But of course we don’t.

Back in 2015, I pointed out several of the inherent issues with the expression “work-life balance”—starting with the fact that people define it in dramatically different ways4. Some treat it as a kind of boundary management problem: If you can just separate work from life cleanly enough—no after-hours emails, for example—you’ve got balance. Others frame it more in terms of control: If you feel in control of your time and choices, you’re balanced, even if work and life are completely entangled.

Those aren’t the only definitions out there. Scholars have identified at least five major conceptualizations of work-life balance, each with its own assumptions and limitations (Kalliath & Brough, 2015; Sirgy & Lee, 2018):

Equal distribution: Balance means splitting time and energy evenly across roles. Great in theory or for some jobs, but real life rarely distributes itself that neatly in many professions.

Compatibility with life priorities: You’re balanced if your work and non-work commitments align with your current goals and values. This one acknowledges that what counts as “balance” will look different for a 28-year-old grad student and a 42-year-old single parent. But it also reveals the trap behind “having it all”: if your priorities conflict, you can’t align them all at once—no matter how much you want to.

Successful role performance: You’ve got balance if you’re meeting expectations in all your roles—at work, at home, wherever. The catch, of course, is that not all expectations are reasonable.

Minimal role conflict: Balance means work and life don’t get in each other’s way. Bonus points if one enriches the other. But with remote work and constant connectivity, this version’s been on life support for a while in many professions.

Perceived satisfaction and growth: Arguably the most modern and flexible definition—it’s all about your sense that your roles are compatible and support your development, given your current priorities. It’s subjective, and that’s the point.

In short, “work-life balance” doesn’t mean one thing. And if we’re all working from different definitions, it’s no wonder the advice often feels mismatched. That’s why I prefer to shift the conversation entirely—from “balance” as a goal to resource allocation as a process (Grawitch, Barber & Justice, 2010).

You see, work and life don’t need to be cleanly separated to be manageable. In fact, they draw from the same limited pool of resources. And understanding how we expend those resources—what demands we face, what we have to give, and how we judge that exchange—is a far better way to make sense of the whole messy picture.

We’ll get to the specifics of PRA in a minute. But for now, the key takeaway is this: work-life balance isn’t one thing. It’s a dynamic state based on your current demands, available resources, and how well they match up. And any attempt to “achieve” balance without understanding those dynamics is probably just a slightly fancier version of treading water.

The Personal Resource Allocation Framework

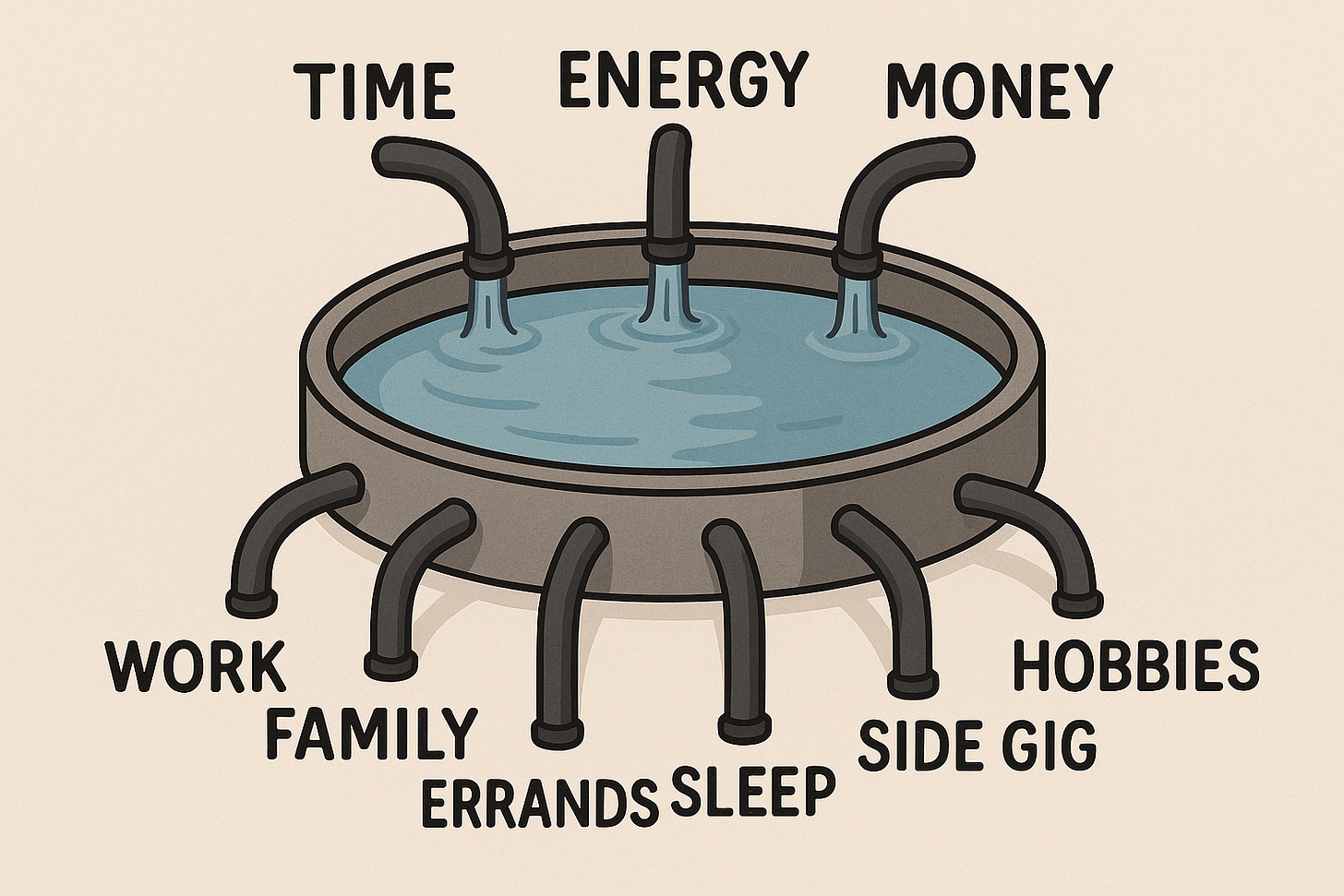

Whether you're leading a team or unloading the dishwasher, you're drawing from the same pool of finite resources. Time and energy are almost always on the hook. And depending on the demand, money might be too. And those are the three basic personal resources we all possess: time, energy, and money.

And so the first assumption behind the Personal Resource Allocation (PRA) framework is this: we don’t have separate resource pools for work and life. There’s just one pool—and everything pulls from it. Work, family, social life, exercise, errands, rest, caregiving, creative projects—they all compete for the same limited set of personal resources.

The second assumption is just as important: there’s no single correct way to allocate those resources. There’s no perfect ratio or ideal work-life mix5. What actually matters is alignment between:

The demands you face (what’s being asked of you),

The resources you have (time, energy, money), and

Your perception of whether you have sufficient resources to respond to those demands.

When those three are aligned, things generally go well. You’re more likely to feel capable, effective, maybe even fulfilled. When they’re misaligned—when you’re stretched too thin, burned out, or constantly scrambling—you feel it. You might not always name it as a “resource allocation issue,” but that’s what it is.

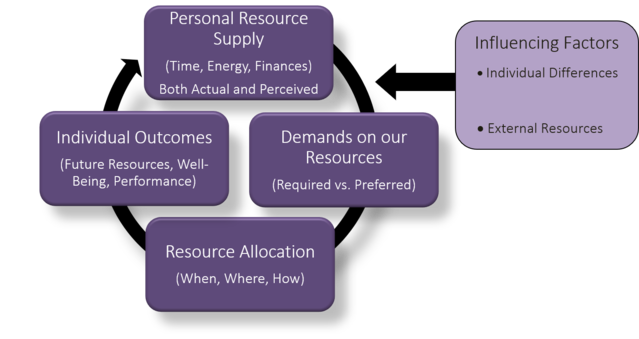

The PRA framework (shown in Figure 1 above) maps out how this plays out over time—and how even subtle shifts in demands or resources can disrupt the process. It’s a useful way to think about what’s actually going wrong when it all starts to feel unmanageable.

What This Means for the Way We Use Our Resources

When you consider Figure 1 and the assumptions behind the PRA framework, a few implications for how we navigate our work-life interface become pretty clear.

The most obvious? Personal resources are limited. We’ve only got so much time, energy, and money to go around. And we constantly make choices—some deliberate, some automatic—about where, when, and how to allocate those resources.

The second implication: all personal resources can be replenished, but only some can be expanded. You get another 24 hours each day, sleep and nutrition help restore energy, and regular paychecks refill the bank account. But replenishment isn't the same as expansion. Energy and money can be expanded—at least to a point. You can increase your energy through better sleep, improved nutrition, or regular exercise. You can grow your financial resources through raises and side gigs. Time, though, is fixed. There’s no productivity hack that makes the day longer. And while you can shift how you spend your time, you can’t manufacture more of it.

Another implication: any activity that requires your time, energy, or money is a demand. We often associate “demand” with something negative, but that’s not quite right. Even the things we want to do—like going for a walk, reading a novel, or having dinner with friends—demand resources. We're just more willing to expend our resources on things we enjoy than on things we do out of obligation. Still, they all pull from the same pool. And managing our personal resources isn’t just about reducing unwanted demands—it’s also about managing the ones you actively choose.

We also need to acknowledge that personal resources are interdependent. You see this in a few key ways:

Most demands require both time and energy. The relationship isn’t perfectly linear—some tasks are exhausting but quick; others are time-consuming but relatively easy—but most demands show a fair amount of overlap.

You often need time and energy to generate money. But you can also use money to conserve time and energy. That’s what we usually mean when we talk about “buying time”—outsourcing something that would otherwise drain your time or energy.

And time can be spent on activities that actually replenish energy—like sleep or nutrition.

Finally, idiosyncratic (or influencing) factors shape how you allocate and experience your resources. Some people find social interactions energizing; others find them draining. Some have strong support systems, helpful technology, or access to external resources that make things easier. But those external resources aren’t free. They almost always require a prior investment of time, energy, or money. Social support usually comes from having built relationships over time. And services that save you time—like meal kits or house cleaning—are just real-time exchanges of financial resources to protect your time or energy.

Understanding these implications isn’t just an academic exercise—it’s a necessary foundation for making better decisions about how we manage our work-life interface. If we don’t fully grasp how our resources operate, how they interact, and how they’re shaped by both our choices and our circumstances, we’re left trying to solve the wrong problems—or applying the right solutions in the wrong places.

Making Decisions to Improve Your Work-Life Interface

A lot of advice on work-life balance falls into the same traps. First, it tends to offer universal solutions, as if the same strategies apply equally to a nurse working night shifts, a parent juggling two part-time jobs, and a fully remote tech worker with flexible hours. Second, it often frames these strategies as a way to achieve balance—as though it’s a fixed destination rather than something you manage over time. And third, it tends to ignore a host of inconvenient realities: some demands aren’t negotiable6, resource limits aren’t always self-imposed, and not everyone has the same resources available to manage their work-life interface.

So rather than offering a blueprint or some sort of prescription for achieving work-life balance, what follows are a few diagnostic suggestions—ways to spot where your resource allocation might be misaligned, and how to start making better decisions from wherever you actually are.

Notice when things aren’t working. If you’re consistently feeling anxious, frustrated, tired, or irritated—especially about demands you can’t seem to get ahead of—it’s a signal that your personal resources aren’t aligned with what life is asking of you.

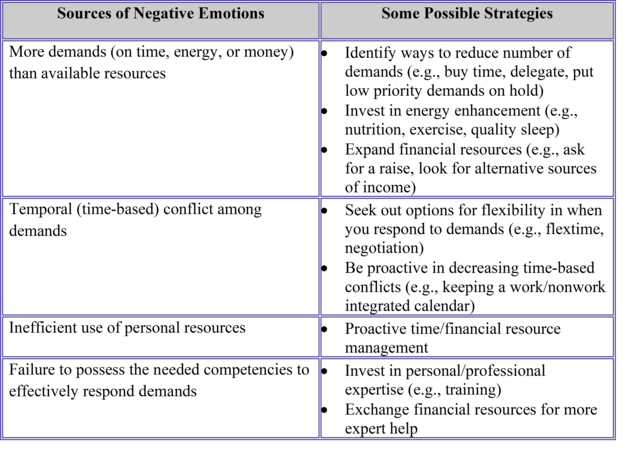

Figure out where the misalignment is. Those negative emotions often stem from one or more of the following:

You’ve got more demands than resources (time, energy, or money).

The timing of your demands is in conflict (everything’s due now).

You’re using your resources inefficiently.

You’re lacking the tools or skills needed to manage what’s on your plate.

Any one of these can create strain. The trick is figuring out which one (or which combination) is creating the biggest drain.

Look for leverage points. Once you’ve identified the misalignment, the next step is to think about what can change. That might mean reducing demands (saying no, delegating, hitting pause on a side project), expanding resources (getting better sleep, asking for help, carving out time to recharge, or seeking out additional income), or managing your existing resources more effectively (rethinking routines, engaging in more effective time or financial budgeting, setting firmer boundaries). You don’t need to overhaul your life; you need to spot where a small change might shift the equation (Table 1 provides some possible strategies).

Try something—just not everything at once. If you come up with ten ideas for how to improve your situation, don’t try to implement them all. Pick one or two high-impact adjustments and see how they affect your resource balance. Once those are in place, reassess. Are you still feeling overdrawn? Has anything improved? What still needs attention?

There’s no perfect formula for getting work and life to play nicely together. But if you can shift the question away from “How do I achieve balance?” and toward “Where are my resources going—and is that working for me?”, you’re in a much better position to make deliberate, sustainable choices. It might not make your life feel balanced in any cosmic sense—but it’ll probably feel a lot more manageable.

That’s actually only about 3 million more than when I wrote the original version of this in 2021, and, honestly, I’m a bit surprised it hasn’t been a bigger jump.

Myself included—even though I’ve learned a lot from studying this issue for over 20 years.

This is one of those claims that, while occasionally validated in polls, tends to get a bit overblown. Perhaps I’ll unpack it more the next time it bubbles up in the news cycle. For now, I’ll just say this: I doubt anyone has ever said, “I don’t care how much you pay me, just so long as I have work-life balance.”

I will also note here that I dislike the expression work-life balance and instead prefer work-life interface because it isn’t focused as much on separating work and life but examining the (in)compatibilities between the two broad life domains.

One of my biggest pet peeves is that a lot—and I mean almost all—of the theory and research on work-life balance assumes that work is the sole source of bad things in the work-life interface. As if everything outside of work is inherently restorative, frictionless, and waiting with open arms. It’s not.

Who here gets to tell their supervisor that they won’t be attending a mandatory meeting because they just don’t have the time? Probably not many of us.

I liked the allocation term and it adds the intentionality aspect as well. Personally, I have never liked the term work-life balance myself as well https://open.substack.com/pub/apoorvaadeshpande/p/work-life-balance-a-false-dichotomy

I've often felt there's something wrong with the phrase and general idea of "work-life balance" as though work might be a problem, like a necessary evil. This reframing in the sense of Personal Resource Allocation is really neat, and long overdue one might add. You're applying time-tested common-sense ideas in economics in this reframing while adapting them to this space. I think this is essential reading for everyone.