Navigating Decisions with Heuristics

Why we can’t escape heuristics—and why we shouldn’t want to.

You can also hear AI Matt’s summary of the piece below.

In previous posts, I’ve explored how heuristics simplify decision making and how they are related to but distinct from biases. While much has been written about the benefits and drawbacks of heuristics, what often gets lost in the conversation is just how fundamental they are to every decision we make. We don’t choose whether to use heuristics—they are, quite simply, the only way we can make decisions. What do vary are (1) which heuristics we employ, (2) the amount of information those heuristics make use of, and (3) the extent to which the information we rely on serves us well.

Recently, I found myself searching for resources to help me teach a more practical approach to using heuristics. It seemed most student understood heuristics to be “mental shortcuts” or “rules of thumb” and that they there were essentially synonymous with intuitive, error-prone decision making. When I began exploring what was floating around the internet, I soon understood why. A lot of what exists represents oversimplified explanations, vague generalizations, and similar lists of ‘common heuristics’ presented with little depth or context. Many glossed over the complexities that make heuristics indispensable in real-world decision making1.

In this piece, I want to go beyond the surface and examine what happens when heuristics work well, when they fall short, and how understanding their nuances can make us more effective decision makers. Far from being mere cognitive tricks, heuristics form the backbone of our decision-making process, whether we're choosing what to eat for dinner or making high-stakes business decisions. The key isn’t to avoid heuristics—it’s to ensure we’re using heuristics that are well-suited to the context.

The Simplistic Narrative of Heuristics

If you perform an internet search for the term heuristic, the first five pages of results are likely to be one of four primary types of sources: (1) dictionary definitions, (2) the Wikipedia page on heuristics2, (3) a smattering of academic articles written about the ecological rationality of heuristics, and (4) sources that discuss heuristics the way Decision Lab does:

While academic articles on the ecological rationality of heuristics rebut oversimplified views, they often fall short in addressing their practical application. These articles sometimes overemphasize the conditions under which heuristics work well, glossing over their limitations and failing to articulate how heuristics affect all decision making.

This gap leaves the general audience with sources like Decision Lab, but there’s several inherent flaws in the way such sources discuss heuristics:

They imply heuristics are used only as a part of intuitive decision making, a myth I dispelled in a prior post3.

They conflate heuristics with biases, which obscures their distinct roles in cognition.

They focus narrowly on specific heuristic rules—like the representativeness heuristic or the availability heuristic—often highlighting their misuse without considering context4.

They portray heuristics as bugs in human decision making rather than features, which amounts to bullshit, as Smets (2024) so eloquently argued.

Yet, the most fundamental flaw—a fatal one—is the portrayal of heuristics as optional. These sources suggest that by engaging in deliberate, analytical thinking, we can sidestep heuristics altogether. This assumption fundamentally misunderstands the nature of decision making and obscures the broader role heuristics play in shaping all decisions.

As Herbert Simon (1957) explained through his concept of bounded rationality, we are limited in how much information we can process at any given time. Heuristics, as Gigerenzer and Gaissmaier (2011) argued, are strategies designed to navigate this limitation by ignoring part of the available information to make decisions more efficiently. In other words, heuristics aren’t just one way to make decisions—they are the only way we can make decisions.

The framing of heuristics as an optional shortcut not only misrepresents their role but also undermines their value. This narrative encourages a bias against heuristics, framing them as error-prone mechanisms rather than indispensable tools. When understood and applied properly, heuristics allow us to effectively navigate the complexities of real-world decision making with efficiency and adaptability.

To improve how we think about heuristics, we must first acknowledge their inevitability. Rather than asking whether we should use heuristics, we should focus on understanding how to select and refine heuristics to suit the context. Whether we're making quick, intuitive choices or engaging in deliberate analysis, heuristics play a central role. The question isn’t whether to use them, but how to use them effectively.

The Breadth of Heuristics

Popular discussions of heuristics often reduce them to a handful of narrow examples, like the availability or representativeness heuristics. These portrayals perpetuate the misconception that heuristics are merely cognitive shortcuts prone to predictable errors. But they miss the mark entirely.

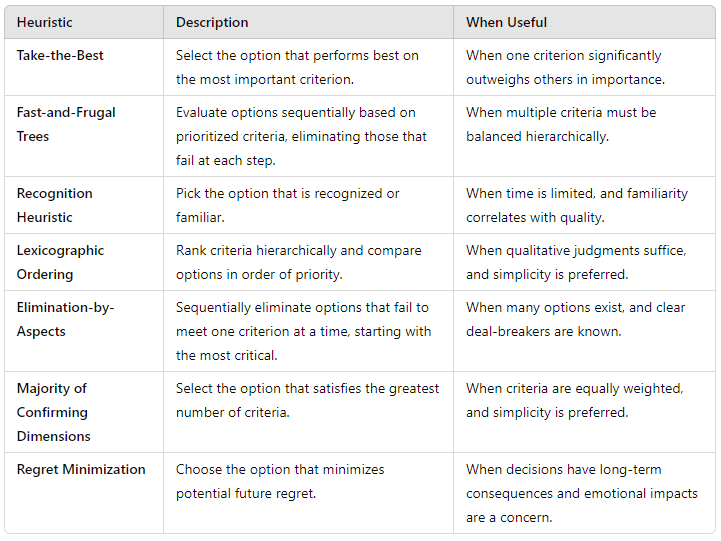

Heuristics are far more varied, nuanced, and context-dependent than most sources acknowledge. They span a wide range of decision-making strategies that are tailored to different scenarios and constraints. To illustrate this, consider the following table, which categorizes a small set of heuristics by their purpose and when they’re useful:

While this table only scratches the surface, it highlights the remarkable diversity of heuristic strategies. Some heuristics, like Take-the-Best, are highly focused, making them ideal for situations where a single criterion dominates. Others, such as Fast-and-Frugal Trees or Lexicographic Ordering, help balance multiple factors, depending on whether simplicity or precision is prioritized.

Even heuristics frequently critiqued as flawed, such as the representativeness and affect heuristics, offer substantial utility. The representativeness heuristic can help us make quick judgments about probabilities or categories when detailed information is unavailable, such as assuming a well-dressed person at a conference is likely a conference attendee. The affect heuristic leverages our emotional responses, which can be particularly useful in decisions where time is limited and one’s affective preferences are a reasonable basis for judgment, such as choosing a restaurant based on how much you enjoy its cuisine.

And the utility of heuristics extends beyond isolated scenarios. Heuristics aren’t just tools for individual judgments; they underpin nearly every aspect of our decision-making process. They guide the procedures for deciding—deciding how we will make our decision (e.g., using fast-and-frugal trees)—and the actual act of deciding, like determining whether to act (e.g., default heuristic), which choice to act on (e.g., using the take-the-best heuristic), or when to act (e.g., using the certainty heuristic). Recognizing these dual roles highlights the indispensability of heuristics in navigating decisions—both simple and complex.

Heuristics are also often effectively combined to address the unique demands of a decision. For example, when planning a vacation, you might start with the availability heuristic to recall potential destinations (e.g., places mentioned in recent travel articles or by friends). Next, the affect heuristic helps narrow the list to locations that evoke excitement. Finally, the take-the-best heuristic might guide the ultimate choice by focusing on a single decisive factor, such as cost or reviews.

This sequential layering illustrates how different heuristics can complement each other, addressing distinct aspects of the decision-making process. Each heuristic addresses a specific challenge: generating options, narrowing choices based on preferences, and making the final selection. By integrating multiple heuristics, decision makers can navigate complexity more effectively while aligning choices with their unique goals and constraints. From triaging patients in a hospital to navigating investment decisions, heuristics provide versatile frameworks for addressing both routine and high-stakes decisions efficiently and—usually—effectively.

Missteps in Using Heuristics

The effectiveness of heuristics depends on how they are applied. But this doesn’t mean we apply heuristics well all the time. In fact, it is not uncommon for us to make some missteps when it comes to using various heuristics. Such missteps generally occur for one of three reasons:

We employ heuristics that are poorly suited to the situation.

The scope of our heuristics are either too narrow or too broad.

Our heuristics rely on inaccurate, irrelevant, or misleading information.

The first of these missteps occurs when we employ heuristics poorly suited to the specific decision context. While heuristics simplify decision making, their effectiveness depends on how well they match the nuances of the situation. For instance, the recognition heuristic—where decisions are based on familiarity—might perform well in a familiar grocery store but falter in an unfamiliar one. Similarly, the take-the-best heuristic, which focuses on a single dominant criterion, is far more effective when applied to a refined shortlist of new cars than when used to navigate an overwhelming list of hundreds. Identifying when a heuristic fits the context is important for leveraging its strengths effectively.

The second misstep arises from mismanaging the scope of information used in heuristics—either relying on too little or too much information. Narrow heuristics that focus on only one or two criteria can oversimplify decisions5. For example, a homebuyer who prioritizes price alone might overlook other vital considerations, like neighborhood safety or school quality unless that single criterion is used solely to make a selection from a shortlist of options. Conversely, overloading a decision with too many criteria can lead to decision paralysis, undermining the efficiency heuristics are meant to provide, making it difficult to reach a final decision. For example, attempting to weigh ten equally important factors when choosing to buy a house can make the process unmanageable, especially when options vary significantly across those criteria. Effective heuristic use strikes a balance, integrating enough information to support a well-informed choice without overcomplicating the process.

The final misstep occurs when heuristics rely on flawed or irrelevant information. This can manifest in two ways: (1) the information itself is inaccurate or misleading, or (2) the information, while accurate, is poorly suited to the decision at hand. For example, choosing a diet based on health claims from an unverified source can result in poor outcomes if the claims are false. Alternatively, prioritizing the color of a car over its price or reliability might result in a choice that later conflicts with long-term financial or practical needs. While the information about the car's color is accurate, overemphasizing its importance can lead to a decision that is misaligned with broader goals, such as staying within budget or ensuring dependable transportation. To mitigate this risk, decision makers should critically assess both the accuracy and relevance of the information they use, ensuring it meaningfully contributes to the decision at hand.

Algorithms as a Complement to Heuristics

A key theme underlying heuristic missteps is our bounded rationality—our inherent limitation in processing vast amounts of information. Heuristics help us navigate this limitation by allowing us to focus on a subset of information, but it can be difficult to synthesize vast amounts of information in ways that allow us to make use of that information effectively. This is where algorithms can complement heuristics. By providing rule-based, step-by-step procedures, algorithms excel at handling large datasets, applying consistent criteria, and delivering precise outputs—capabilities that enhance and expand the effectiveness of heuristics.

For example, consider the challenge of selecting a car from hundreds of available models. Using a heuristic like take-the-best might oversimplify the decision, focusing on a single criterion and ignoring other potentially important criteria. In this situation, an algorithm, such as those available on websites like Autotrader, could filter and rank cars based on broader criteria like price, fuel efficiency, and safety ratings, narrowing the choices to a manageable shortlist. With this shortlist in hand, heuristics like take-the-best or elimination-by-aspects can then effectively aid in making the final selection.

Heuristics and algorithms are not competing approaches but complementary tools in decision making. Algorithms excel at handling large datasets and applying consistent criteria, making them useful aids when where heuristics might struggle. When faced with overwhelming volumes of information or the need for consistent, objective criteria, algorithms can simplify the process by filtering, ranking, and organizing options.

However, heuristics remain essential for deciding whether, when, and how to use algorithmic decision support. Algorithms can provide structured outputs, but they cannot decide for us how to interpret, prioritize, or act on those outputs6. Whether we trust an algorithm’s recommendation, modify it, or seek additional information often hinges on heuristics. For example, the default heuristic might guide us to accept the algorithm’s output, while the affect heuristic could lead us to weigh our emotional response to its suggestions.

By understanding the interplay between heuristics and algorithms, decision makers can better leverage their respective strengths. Algorithms are most effective when used to handle complexity and provide structure, while heuristics shine in areas requiring human judgment, contextual adaptability, and subjective prioritization. The key lies in recognizing when and how to integrate algorithms into the decision-making process.

Improving How We Use Heuristics

Heuristics play an important role in all decision making, but there’s always room to improve how we apply them. One approach is calibrating our use of heuristics with existing evidence. For instance, before relying on the availability heuristic to judge a product’s popularity, it’s worth asking: “Am I only considering recent examples? How representative are they?” Such reflection can reveal blind spots, guide our choice of heuristics, and encourage us to incorporate information that enhances both the quality of our decisions and our confidence in them.

Equally important is ensuring that the heuristic fits the context. Different situations call for different strategies. In a high-stakes medical decision, for example, relying solely on the affect heuristic might lead to an emotionally satisfying decision but one we ultimately regret. Incorporating complementary evidence or criteria can create a more well-rounded foundation for action, particularly when the stakes are significant.

Being deliberate about how we combine different heuristics can also enhance decision making. For example, someone deciding which new smartphone to purchase might start with the recognition heuristic to choose a broad category of phone (e.g., iPhone or Android) based on prior experience. Then, the elimination-by-aspects heuristic can be used to filter out models lacking essential features like a high-quality camera or long battery life. Finally, the take-the-best heuristic can be used to make the final decision, using a single criterion, such as price or customer reviews, as the basis for it. This layered approach leverages the strengths of multiple heuristics, enabling them to handle a complex decision while mitigating individual weaknesses.

Experience itself is also useful for helping us to improve heuristic use. Reflecting on past decisions can help identify patterns of success and failure, offering insights into when certain heuristics work well and when they fall short. While this refinement process often occurs unconsciously—such as when trial-and-error heuristics help drivers learn new ways to navigate traffic congestion—it can be enhanced through deliberate reflection. Actively evaluating decision outcomes, questioning heuristic suitability, and considering alternative strategies can make heuristic use more intentional and effective across diverse contexts.

Finally, understanding and managing the inherent trade-offs of heuristics can improve how effectively we apply them. In time-sensitive decisions, speed may take precedence over accuracy, leading to narrower heuristic rules. Conversely, complex or high-stakes scenarios often require more deliberative processes, broader heuristic rules, or the integration of additional information. Aligning heuristic use with the specific demands of a situation increases their effectiveness. By acknowledging these trade-offs, decision makers can tailor their use of heuristics to the unique challenges of different decision contexts, enabling informed and adaptable decisions in an ever-evolving world.

Most of what didn’t seem to offer a view of heuristics as being these flawed decision-making strategies made reference to the prior work of Gerd Gigerenzer and his colleagues (or were written by them), which was what I wanted to integrate but in a more applied way.

Which is actually a reasonable source.

This myth persists because most of these sources are themselves grounded in dual-process theory.

What’s interesting about lab studies that show how “flawed” these heuristics can be is that (1) they offer no other more sophisticated ways for participants to make decisions—leaving them little choice but to rely on those heuristics to decide—and (2) the decisions being made are inconsequential, such as deciding whether more words in the English language start with K or have K as the third letter.

Some heuristics, like take-the-best, are inherently narrow by design, ensuring that if Misstep #1 applies, Misstep #2 will also apply. Other heuristics, such as fast-and-frugal trees or elimination by aspects, are more flexible and can vary in their breadth. However, as Gigerenzer et al. (2022) argue, sometimes such strategies can work well, even if it may seem broader heuristic strategies should be applied.

Additionally, algorithms themselves are not infallible. Their effectiveness depends on the quality of the data they process, the criteria they apply, and how they apply those criteria. Moreover, algorithms may not effectively handle more sequential decision-making processes, such as those involved in fast-and-frugal trees, as discussed more by Gigerenzer et al. (2022).