When Experts Overstep

Navigating the Sweet Spot Between Insight and Overreach

A previous version of this post was published on Psychology Today.

You can also hear AI Matt’s summary of the piece below.

Modern technology has made access to information easier than ever. In a split second, we have access to a seemingly infinite amount of information on almost any topic we can imagine. And social media makes it easier than ever before to glean insight and wisdom from experts in nearly any field.

But with this unprecedented access comes an important question: How do we evaluate the quality of the information we receive? While some expert insights offer tremendous value, others stretch beyond the boundaries of their expertise, leading to misleading or oversimplified conclusions.

This article explores the nuances of expertise, the role of skilled intuition in producing valuable insights, and how to recognize the limits of an expert’s claims—because even experts don’t know everything.

The Expertise Bubble

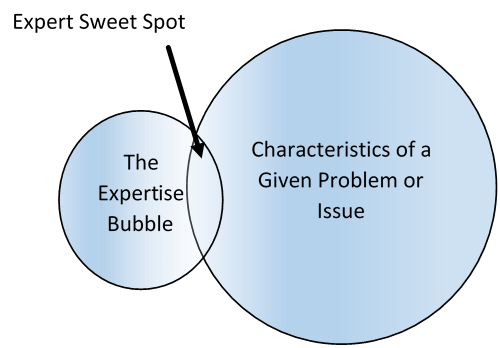

Every expert operates within a unique frame of reference shaped by their training and experiences. As such, practitioners’ expertise and experience only really apply directly to a finite amount of subject matters and in specific situations or settings—what we can think of as an expertise bubble. We can visualize this dynamic as a Venn diagram. On one side, you have the issue under consideration. On the other, you have the practitioner’s expertise, which includes not only their subject knowledge but also the amount of experience they have in applying that knowledge to the given problem.

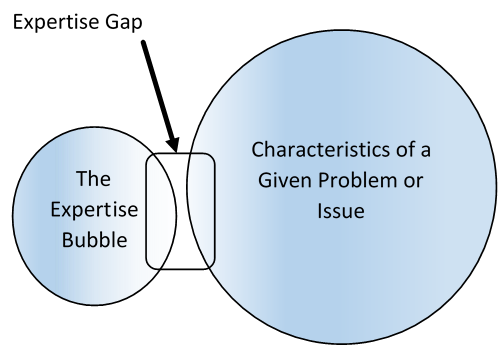

The intersection of these two areas represents the expertise sweet spot, where an individual’s insights are most likely to be accurate and valuable (see Figure 1). The further the issue lies from this overlap, the greater the gap between the practitioner’s actual expertise and the quality of the insights produced based on the application of that expertise1 (see also Figure 2).

For example, consider someone very close to you, perhaps a spouse. You may have an extraordinary amount of experience with that person in their role as a partner, making you an expert on their behavior in that context. However, your insights might be far less reliable when applied to their workplace behavior, which lies outside your expertise bubble.

Similarly, imagine a nutritionist who specializes in dietary planning for athletes. If asked to provide advice for a patient managing diabetes, their knowledge of general nutrition might offer some guidance, but it may not fully account for the complexities of blood sugar management. Their expertise sweet spot lies in sports nutrition, and while they can contribute to the discussion, their insights on diabetes might require further support from someone whose expertise specifically aligns with managing chronic illnesses or even specifically diabetes.

Skilled Intuition: When Experience Drives Judgment

One of the most compelling aspects of true expertise is skilled intuition—the ability to make rapid, accurate judgments based on a wealth of prior experience (Kahneman & Klein, 2009). Skilled intuition isn’t guesswork; it’s the result of repeated exposure to similar problems, allowing experts to recognize patterns and respond effectively without extensive deliberation.

As Herbert Simon (1957) explained, humans operate under bounded rationality—we’re limited in how much information we can process. Skilled intuition operates within these constraints, enabling experts to use heuristics to make decisions efficiently by focusing on the most relevant information.

Gary Klein’s Recognition-Primed Decision (RPD) model offers a clear example of how heuristics underlie skilled intuition. In the RPD model, experts make decisions by rapidly recognizing similarities between a current situation and prior experiences. The recognition heuristic simplifies decision making by identifying the most familiar or salient option as the starting point for action. For instance, a seasoned firefighter arriving at the scene of a blaze might instinctively know the safest way to contain the fire. This decision isn’t arbitrary; it’s grounded in years of exposure to similar scenarios, where patterns have been internalized and can be applied quickly and effectively.

Skilled intuition works well when the situation aligns closely with the expert’s prior experience—within their expertise sweet spot. However, problems arise when experts venture into unfamiliar territory. Their intuitive judgment may not translate as effectively because they lack recognizable patterns to draw upon. For example, a financial advisor with deep experience in managing individual wealth might falter when offering advice on corporate investment strategies. While both fall under the broader umbrella of finance, the nuances of these domains differ, and the advisor’s intuitive judgment may not translate as effectively.

Recognizing the limits of skilled intuition is essential, as even experts can misjudge situations when operating outside their domain, leading to overconfidence or flawed conclusions. By understanding the boundaries of their expertise, practitioners can better assess when to trust their intuition and when to seek additional information or collaborate with others.

Recognizing Overreach and Misleading Claims

There is a common fallacy to which people fall prey, especially in uncertain situations: appeal to authority. Although the claims by experts may be based on skilled intuition and/or specific evidence related to a given issue, this does not mean all such claims fall into this category. Even experts are prone to weighing in on topics where there is a gap between their expertise and the problem or issue under consideration. This doesn’t mean dismissing experts outright but rather learning to critically evaluate their insights—especially in areas where they may be stretching their expertise too far.

Here are some common red flags to watch for:

Claims Outside Their Expertise: When experts comment on issues only tangentially related to their specialization, caution is warranted. For example, a biologist specializing in marine ecosystems might weigh in on agricultural policy due to shared themes of environmental conservation. While the biologist’s perspective is informed, it may lack the depth or specific understanding of someone who works directly in agricultural systems.

Overconfidence in Complex Issues: The more complex a problem, the less likely any single explanation fully explains. If an expert presents conclusions with absolute certainty—particularly in areas involving intricate systems or human behavior—it’s worth questioning whether they’ve oversimplified the issue. For example, an expert who claims to have the answer for improving happiness or decreasing stress likely doesn’t.

Reliance on Extreme Scenarios: Experts who lean heavily on best-case or worst-case scenarios to justify their claims may be skewing the conversation. While these examples can be compelling, they often fail to represent the full spectrum of possibilities. It is often easy to lean on extreme examples and use those as the basis for broader arguments (e.g., the imminent terrorist attack being used as grounds for the morality of torture). Extreme examples, though, are seldom applicable to most cases, nor do they represent the most likely outcome. Therefore, if the expert’s claims are based on the best- or worst-case scenario, we should probably be a little bit more skeptical of those claims. For instance, a financial advisor warning that failing to invest in a specific stock will result in missing out on life-changing wealth is relying on an extreme, best-case scenario that doesn’t account for the many other potential outcomes, including losses.

Contextual Mismatches: An expert using evidence from one context to justify claims in a vastly different setting might be stretching their expertise. For instance, a psychologist using findings from small-scale laboratory studies to explain the behavior of large populations in a societal context may overlook critical differences between those settings.

Counterintuitive Assertions: While intuition has a bad reputation, thanks largely to laboratory studies on cognitive bias, in reality, intuition often works out in our favor. We make a lot of everyday decisions based on intuition and most of them work out because we’ve learned from prior mistakes. If a claim smells fishy, it probably requires deeper investigation before we accept it as valid. For instance, an expert claiming that increasing screen time improves sleep quality might initially sound completely at odds with what we know about blue light and sleep disruption. While such a claim might have niche backing, like specific apps or devices designed to aid relaxation, it would require deeper investigation to validate or contextualize.

Navigating Expert Advice

It’s important to remember that not all overreach is malicious. Many experts genuinely seek to provide helpful insights, even when stepping slightly beyond their primary domain. The key is to approach expert claims with a balanced mindset: neither dismissing them outright nor accepting them uncritically. By cultivating critical thinking and asking the right questions, we can navigate expert advice more effectively—balancing healthy skepticism with an openness to learning from those who genuinely seek to inform.

This may occur because their subject matter expertise doesn’t align with the specific issue at hand or because the contexts in which their expertise applies differ from the current situation.