Batting .300 Against Uncertainty, Revisited

Connecting intuition, data, and the psychology of decision making in the MLB postseason

You can also hear AI Matt’s summary of the piece below.

For those who don’t know, I’ve been a baseball fan since I was a kid. But as I got older and started studying psychology more seriously, I began to see the game differently. Baseball wasn’t just entertainment—it was a live demonstration of human behavior. And when I eventually found my way into studying and teaching decision making, the connection became even clearer: baseball is a nearly perfect showcase for how people make choices under uncertainty.

As I wrote in Batting .300 Against Uncertainty, baseball is a near-perfect lab for watching people make choices under pressure. Every play begins with a pitch, and every pitch moves the game forward in its own way. There’s no clock ticking in the background—no automatic motion unless something happens on the field. Each pitch is its own decision space: what to throw, where to position, whether to swing. The inning, the score, the matchup, the number of outs—they all shift the calculus.

So, when I saw Jeff Dodd’s (2025) headline—“Should managers rely on data or intuition?”—I winced. It’s a great headline, but a bad question. Baseball, like most of life, doesn’t force us to choose between the two. It forces us to decide how far to trust what we already think we know—and when the moment calls for digging deeper.

I’d planned to write a post in response, but it quickly became clear that much of Dodd’s article didn’t align with its own headline. And as I thought through how to connect to it meaningfully, I realized I’d already written most of what I wanted to say—just across different posts. So instead of starting from scratch, this piece pulls those threads together: filling in a few of the gaps in Dodd’s article, expanding on some of his points, and adding a bit of decision-making perspective where it fits. To his credit, Dodd does better than most. He acknowledges that intuition and data aren’t necessarily opposites, quoting Harvard’s Jennifer Lerner: “Intuition is often the distillation of years of experience with data and patterns.” Exactly right.

That’s why the “data versus gut” framing misses the point. Intuition isn’t the opposite of analysis; it’s what happens after enough analysis has been absorbed. A manager’s gut is just experience that’s been processed, tested, and compressed over thousands of innings. The real question isn’t whether intuition is reliable—it’s whether that intuition is calibrated to the situation.

The False Dilemma

Dodd’s framing—data on one side, intuition on the other—echoes the same dual-process model that’s dominated decision-making research for decades. Fast versus slow. Gut versus graphs. It’s tidy, and like most tidy stories, it’s wrong.

As I argued in The System 1 vs. System 2 Debate, those labels oversimplify how people actually decide. In one study I mentioned there (Couchman et al., 2016), students were far more accurate on test items when they felt confident in their initial responses—confidence that stemmed from genuine familiarity with the material. When they weren’t confident, their answers hovered near chance. The point isn’t that confidence guarantees accuracy; it’s that intuitive accuracy rises and falls with the quality of the experience underneath it. Intuition isn’t inherently flawed—it’s only as good as the knowledge and feedback that informs it.

Dodd gets close to resolving the data-versus-gut debate. He quotes researchers who note that intuition is the distillation of experience with data and patterns. But the article still treats data and intuition as if they were parallel tracks that need to be balanced. If intuition grows out of those experiences, then it isn’t a separate mode of thinking to balance against data—it’s what happens when data and experience have been absorbed and integrated. The two aren’t rivals; they’re points on the same learning curve and part of one integrated decision-making process.

Where Intuition Comes From

When Dodd quotes Joe Maddon’s old mantra—“Feel is the gift of experience”—he’s actually pretty spot on when it comes to how intuition evolves. Intuition feels sudden, but it doesn’t appear out of nowhere. It’s the product of experience—processed quickly and often silently, grounded in familiarity but delivered without explanation. Over time, repeated exposure to meaningful patterns, combined with feedback about what worked and what didn’t, builds embedded knowledge. As Prietula and Simon (1989) put it, “intuition grows out of experiences that once called for analytical steps.”

Those analytical steps eventually condense into what cognitive scientists call configural rules—mental templates that integrate cues simultaneously rather than one by one (Gobet & Simon, 1996; Shanteau, 1988). Decision makers stop tracking each variable independently and start recognizing whole patterns. Once those patterns are learned, they operate below awareness. We’re no longer reasoning through the logic; we’re seeing what fits.

Maddon’s “hot moment” in Game 7 of the 2016 World Series—asking Javy Báez to bunt with two strikes—wasn’t superstition or recklessness. It was pattern recognition: a read built from years of experience. Could he have slowed down and gathered more data? Maybe. But it’s not clear any new information would have changed the call. The outcome made it look wrong, but (1) his reasoning appears defensible and (2) it’s questionable whether a different decision would have produced a better result.

When to Trust It—and When to Dig Deeper

Dodd’s story about Ned Yost captures this tension perfectly. In the 2015 World Series, Yost led off Alcides Escobar—a move that made no sense on paper. The analytics said Escobar didn’t get on base enough to justify the role. But Yost had also seen a different pattern: the Royals tended to win when Escobar hit first.

He wasn’t ignoring data; he was interpreting which data mattered most. His confidence came from knowing when the pattern of team success told him more than the individual numbers did. Following the script would have meant deferring to the safer, more conventional logic. Trusting his gut, in this case, meant trusting the context—the larger pattern that felt meaningful because it was grounded in lived experience.

That’s what confidence does in real decision making: it acts as a trigger. When our first read of a situation feels well-calibrated—consistent with experience and supported by recognizable cues—we act on it. When it doesn’t, that uncertainty pushes us to slow down, gather more information, and test our assumptions. As I wrote in Why More Evidence Isn’t Always Better Part 3, intuition isn’t the enemy of analysis; it’s what tells us when more analysis is needed.

That whole process is, in itself, a heuristic—a simplified decision strategy for determining when to act and when to think more. As I described in Navigating Decisions with Heuristics, heuristics work by narrowing the evidence field: identifying which cues to use, how to weigh them, and when to stop searching for more. The recognition heuristic often sparks our initial intuition, and we then—usually without conscious awareness—apply a fast-and-frugal tree to decide whether to trust that response or dig more deeply. Even the choice of where to dig is guided by experience—another layer of heuristic learning built over time1.

Dodd quotes Laura Huang’s line that “intuition whispers while data screams.” It’s a good metaphor, but it only captures part of the process. The goal isn’t to shut out the data’s noise or to romanticize the whisper. It’s to recognize what the whisper means: sometimes it says “you’ve seen this before, go with it,” and other times it says “something’s off, dig deeper.”

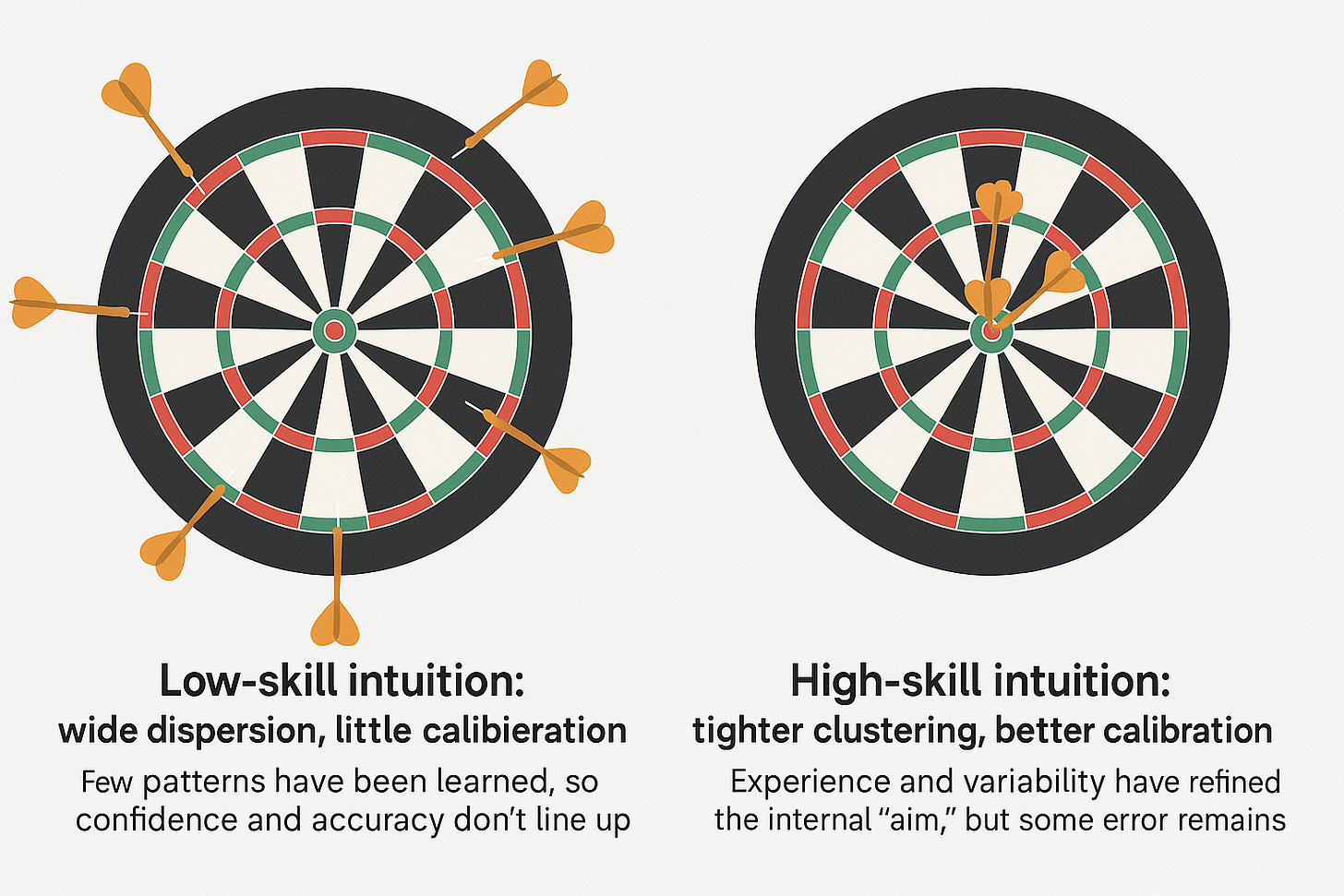

Intuition serves us best when three things converge—expertise, experience, and variability. Expertise gives intuition its foundation; experience provides the feedback that refines it; and variability stretches it, helping us recognize when familiar cues no longer fit. When those pieces align, intuition becomes well-calibrated—probabilistic, not perfect, but reliable enough to guide quick judgment.

Think of intuition like throwing darts (my apologies for jumping sports briefly, but I couldn’t come up with a terrific baseball metaphor here). Each intuitive judgment is a throw. For novices, the darts scatter—some hit the board, some miss entirely. As expertise and varied experience grow, the throws start clustering closer to the center. They never land in exactly the same place, but the pattern tightens. That spread matters. Even skilled intuition produces variance—it just does so around a more reliable target.

That’s what makes decision making in baseball such a useful mirror for the rest of us. Each inning, each situation, is a test of calibration: is my read on this moment good enough to trust, or has the context shifted enough that I need to check again? The challenge isn’t choosing between data and intuition—it’s learning when one should hand the ball to the other.

The Trade-Off

Dodd notes how managers live under a microscope, forced to explain every decision once the outcome is known. That scrutiny creates a paradox: the better a person’s intuition becomes, the harder it is to explain.

As I argued in You Can’t Always Think Your Way to the Right Answer, intuition isn’t a mystical opposite of logic—it’s reasoning that’s been practiced into fluency. Over time, analytical steps get condensed into patterns we can recognize at a glance. Much of expert decision making runs on those tacit structures—configural rules and associations that don’t translate neatly into words. When we’re asked to explain them later, we reconstruct a plausible story, not because we’re hiding anything but because so much of the reasoning happens below awareness.

That’s the part Dodd doesn’t get much into, though I wouldn’t have expected him to. Postgame press conferences sound analytic even when the decision wasn’t, because justification and explanation aren’t the same thing. A manager may genuinely believe the story he tells about why he pulled a pitcher or called for a bunt—but the more that decision was based on intuitive judgment, the more explanation is to be a reconstruction of how it might have happened. The logic is built after the fact, not before it—as I explored more fully in How Did You Get That? The Coherent, the Confident, and the Completely Made Up.

And that’s what makes defending intuitive decisions so tricky. Sometimes the rationale lines up neatly with the decision itself; more often it doesn’t. The story sounds coherent because it has to—it’s how we make sense of actions that weren’t explicitly reasoned through at the time. That doesn’t make the call irrational; it just means the logic we hear afterward may not match the logic that actually guided it2.

That’s the real trade-off. When we make decisions through more conscious reasoning, it’s easier to sculpt a rationale and defend it—though not always convincingly. With intuition, the best we can usually do is build a plausible explanation after the fact, whether or not it truly reflects the reasoning that guided us in the moment. In Maddon’s decision to have Javy Báez bunt, it’s impossible to know exactly what tipped the scales because the process was largely intuitive. In Ned Yost’s decision to lead off Alcides Escobar, we can see where conscious reasoning played a role, but we still can’t know why he chose to weight one set of data more heavily than the rest of the evidence suggesting it was a questionable call.

Process over Outcome

Dodd closes his article by suggesting that experience can close the gap between effortful (or rational, if you really prefer) and intuitive decision making. He’s right, though the harder gap to close is the one between decision quality and outcome quality. Those two things often move in opposite directions. A well-reasoned choice can still lead to a bad result, and a poorly reasoned one can occasionally get lucky3.

That distinction tends to disappear once we know the outcome. When a decision fails, the story we tell afterward almost always assumes that a different process would have changed the result. Maybe it would have. But in the moment, the question is rarely about perfection; it’s about calibration—whether the intuition, the evidence, and the confidence were aligned well enough to justify the call.

That’s why it’s so easy to overestimate how much control we have, especially in environments like baseball. Each decision unfolds in real time, under uncertainty, with feedback that comes later and often says more about chance than judgment. The problem isn’t that managers—or any of us—make “bad” decisions. It’s that we keep grading the process by its aftermath.

The more honest approach is to separate the two. Evaluate the process on how reasonable it was given what was known at the time, not on how it turned out. Maddon’s bunt and Yost’s lineup are both defensible if you look at them that way: one didn’t work, the other did, but each reflected an intuitive read shaped by years of experience and context. The outcomes don’t prove one right and the other wrong; they just remind us that intuition and analysis are both probabilistic games.

Baseball—and decision making more broadly—is never about certainty. It’s about judging, in real time, whether what you know and what you sense are enough to act on. Sometimes the ball finds the barrel. Sometimes it doesn’t. The work is in learning from both without rewriting the past to make one look smarter than the other.

It’s important to keep in mind that our intuition is inevitably biased by our prior experience—that experience become a part of our frame of reference. That’s why variety matters: the broader the range of experiences, the wider the pool of patterns our intuition can draw from, and the less likely we are to miss important cues that would be needed for reliable insight.

And confidence can be a double-edged sword. Once we feel certain enough about an intuitive judgment—no matter how sound it actually is—motivated reasoning can take over, filtering out or discounting evidence that doesn’t fit. At that point, it’s not the quality of the decision that matters, but how tightly we hold onto it.

As I argued in “The Illusion of Perfect Reasoning,” sound reasoning doesn’t guarantee sound conclusions. Deductive logic depends on the premises it starts with, and most real-world decisions rest on inductive inference—probabilistic reasoning built on incomplete evidence. Even the most deliberate process can go astray when the inputs are uncertain.

Good timing. Wondering if Toronto's manager wished he'd read this before relieving with Little against the meat of Seattle's lineup in Game 5. But worked out fine for Toronto, eventually. They get Ohtani beginning Friday. Might be a quick Series though.🤷♂️

Your evaluation of intuition, and decision making more generally, seems closely related to the view we explore in a new series on behaviour and science. The initial post is more philosophical but nevertheless perhaps of interest. Take a look if you have time and interest. Comments welcome.

https://open.substack.com/pub/besci/p/bb1-on-science-and-behaviour-whats?r=1nbjpe&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

"The problem isn’t that managers—or any of us—make “bad” decisions. It’s that we keep grading the process by its aftermath."

Hindsight bias is a harsh mistress...