Risk, Uncertainty, and the Unintended Consequences of Our Choices

Navigating these issues is important for making effective decisions.

This post represents an integration of two prior posts on Psychology Today1.

Very few decisions we make are guaranteed to work out exactly as we hope. Instead, as I’ve written before, we often base decisions on our assessment of costs and benefits, the likelihood of achieving the desired outcome, and whether that likelihood feels sufficient for us to take the gamble.

To make better decisions, we need to understand the distinctions between risk, uncertainty, and the unintended consequences that can arise from the decisions we make. These concepts play critical roles not just in our personal lives, but also in professional and organizational decision making. By exploring how they intersect, we can better plan for what’s knowable, adapt to what’s unknowable, and build resilience for the unexpected.

Risk vs. Uncertainty: What’s the Difference?

Risk exists when the probability of achieving the desired outcome—or avoiding an undesired one—is less than 100%. Importantly, risk is quantifiable or estimable. For example, we can calculate the probability of not winning the lottery, getting into a car accident, or losing a hand in blackjack.

While risk may be theoretically calculable, the exact amount of risk tends to vary based on relevant contextual factors. For instance, as the comedian Michael McIntyre pointed out, the probability of dying in a shark attack off the coast of Australia may be quite low, but it’s 0% if you choose not to swim there. While such an idea may get laughs, it also highlights that risk isn’t fixed—it can be adjusted upward or downward based on decisions we make and the context in which those decisions occur.

It’s also important to remember that while risk is generally quantifiable, we don’t always know the exact percentage of risk in a given decision. In many cases, we’re left to rely on our perceived level of risk, which may differ from actual probabilities2. As a result, many decisions are based more on subjective perceptions of risk than on precise calculations.

For example, it’s reasonable to assume that the risk of getting into a car accident increases in poorer weather conditions3. However, the extent to which that risk increases depends on several contextual factors, such as the time of day, time of year, and the driver’s age and experience. Most drivers intuitively recognize the elevated risk and respond by either (1) driving more cautiously in such conditions or (2) reducing how much they drive altogether. Generally, the greater the perceived risk, the more likely people are to take proactive—and sometimes extreme—measures to reduce it.

Sometimes, though, our perceptions of risk are skewed. Newly identified risks, recent negative experiences, or traumatic events4 can make certain risks more salient, leading us to overestimate their likelihood. This overestimation can cause us to take extreme steps to mitigate risks, even when such steps may not be warranted—a behavior often linked to loss aversion5. Once risks become less salient, they may fade into the background, leading us to automatize behaviors like putting on seat belts—or, conversely, to become careless when nothing bad has happened recently.

In contrast, uncertainty refers to the unknown or indeterminable. Unlike risk, uncertainty cannot be assigned probabilities because the influencing factors are not fully knowable. For example, a company cannot precisely predict what its industry will look like in five years, making any long-term plan heavily dependent on assumptions. These assumptions, while helpful for scenario planning, cannot provide definitive probabilities.

The distinction between risk and uncertainty matters because misinterpreting uncertainty as risk can lead to decisions skewed by the illusion of calculable risk in situations that are fundamentally ambiguous. Attempting to assign probabilities to the unknowable often results in wildly inaccurate estimates, causing us to either take unnecessary risks or adopt excessive caution.

Consider the launch of new technologies, like early self-driving cars. Developers and regulators often tried to model accident probabilities as if all the variables were known—assuming they could estimate safety based on limited testing data. But these systems operated in open, unpredictable environments where edge cases and human behavior couldn’t be fully accounted for. Instead, we must recognize what is predictable and what isn’t, tailoring our strategies accordingly.

The Framework of Unintended Consequences

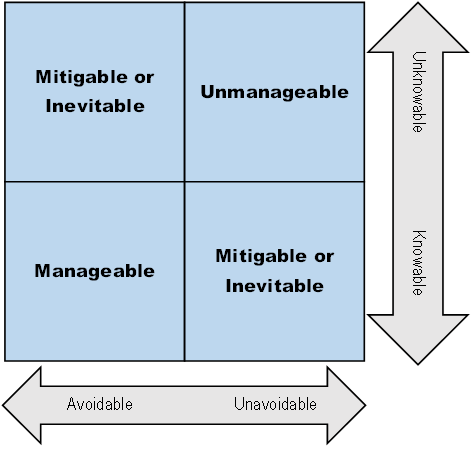

Even when we carefully plan for risks and uncertainties, our decisions often lead to unintended consequences—outcomes we didn’t anticipate or intend. These consequences can be categorized based on two dimensions: knowability (what we can or cannot know) and avoidability (what we can or cannot control). This framework (Figure 1), adapted from Suckling et al. (2021)6, offers a valuable way to understand how unintended consequences arise. But there are three points worth mentioning.

First, there’s a distinction between what is knowable (i.e., capable of being known) and what we actually know. For instance, f you’re packing for a trip, the weather forecast at your destination is knowable—weather apps and forecasts can provide this information. However, if you don’t check the forecast, you won’t actually know what to expect or how to pack appropriately7. This distinction is important in decision making because it highlights that there may be gaps between what could be known and what decision makers take the time or effort to learn.

Second, there’s often a fuzzy line between avoidable and unavoidable outcomes. Consider traffic congestion during your daily commute. While it might seem unavoidable, there are strategies we can employ to reduce its impact, such as leaving earlier, taking an alternate route, or using public transportation. Yet, even with these strategies, some level of congestion might still occur due to unpredictable events like accidents or road closures. So, while some outcomes can be managed to a degree, they’re often not entirely controllable.

Finally, it’s important to recognize that these categories aren’t static. What is unknowable today might become knowable tomorrow as new information emerges. Similarly, what seems like an unavoidable consequence may become avoidable with greater experience or advancements in technology. For example, a business decision that initially resulted in supply chain delays might become more manageable over time as new logistics solutions are developed or as lessons are learned from past disruptions.

These nuances—what we know versus what we don’t, the blurred line between avoidable and unavoidable outcomes, and the dynamic nature of these categories—highlight why unintended consequences often defy simple explanations. To better understand how these outcomes arise, we can classify them into four distinct types based on their knowability and avoidability.

Knowable and Avoidable Consequences: The Manageable Risks

These consequences fall within the realm of risk, as they are both predictable and preventable before they occur (a priori). Their likelihood and impact can be reduced or eliminated entirely if decision makers take proactive steps. When knowable and avoidable risks are not addressed, it’s usually due to a failure of foresight or preparation rather than an inherent inevitability.

For instance, a company planning to implement a new software system knows that employees may struggle with adoption. This consequence is avoidable if the company provides proper training, runs a phased rollout, and gathers early feedback. While some risk will still be present, taking these actions significantly decreases the likelihood of them materializing.

Similarly, in our personal lives, failing to budget can increase the risk of financial instability, but this is an avoidable consequence. By proactively tracking expenses and setting financial goals, individuals can often prevent financial hardship before it occurs. In these cases, risk is present, but because it’s knowable, proactive steps can be taken to manage it.

Knowable and Unavoidable Consequences: The Inevitable Outcomes

These consequences are still predictable—they fall within the realm of risk—but unlike avoidable risks, they cannot be entirely prevented. Instead of elimination, the focus is on managing their impact, as they are inherent to the decision itself.

What makes these consequences unavoidable is that the decision maker must accept them as part of the trade-off for pursuing a particular goal. While mitigation strategies can lessen their impact, they cannot be removed entirely without undermining the decision itself.

A company knows that downsizing will hurt employee morale and result in the loss of institutional knowledge. However, this consequence is unavoidable—no matter how carefully the transition is handled, some negative impact is inevitable. The company accepts the trade-off in exchange for financial stability but can mitigate the damage by offering severance packages, career counseling, and transparent communication.

On a personal level, choosing a demanding career path (such as medicine or law) comes with stress and reduced leisure time. These are unavoidable trade-offs—you can’t eliminate them entirely. However, you can mitigate their impact by setting boundaries, managing stress, and building a strong support system.

Knowable and unavoidable consequences are not failures of foresight or preparation. Instead, they are realities that come with certain decisions. The best strategy is not to try to eliminate them, but rather to accept and plan for their effects, minimizing their impact where possible.

Unknowable and Avoidable Consequences: The Unexpected Risks

This category highlights the limitations of risk-based thinking and the presence of uncertainty. Unlike the first two categories, where risks can be estimated, these consequences emerge from unknown factors that only become apparent over time—meaning they initially fall under uncertainty but later transition into manageable risks once they become known.

For instance, when a company launches a new product, it cannot predict every possible market reaction. A competitor might release a superior product, or customer preferences may shift unexpectedly. While these risks were unknowable at the outset, they become avoidable with ongoing market analysis, flexible strategy adjustments, and contingency planning.

In personal contexts, long-term travel planning can involve unknowable risks such as sudden political instability or unexpected health concerns. While these risks cannot be predicted upfront, travelers who remain informed and adaptable—such as by purchasing flexible airline tickets or securing travel insurance—can avoid some of the negative consequences once the risks become apparent.

This category demonstrates how uncertainty can transform into risk—and how adaptability is key to converting initially unknowable risks into avoidable ones.

Unknowable and Unavoidable Consequences: The Pure Uncertainties

These consequences fall into the domain of pure uncertainty, as they are neither predictable nor avoidable. They represent situations where we lack the information to make accurate forecasts, and no amount of risk mitigation can prevent their occurrence.

For example, a sudden geopolitical crisis—such as an unexpected war or trade embargo—can drastically impact global supply chains, raw material costs, and economic stability. These disruptions are unknowable because they arise from complex political and economic factors beyond any one company’s control. They’re also unavoidable because businesses cannot prevent them, no matter how well they plan. However, companies that diversify their supply chains, establish regional sourcing alternatives, or maintain strategic inventory reserves are better positioned to absorb the impact and adapt when such uncertainties arise.

Similarly, in personal decision making, unknowable and unavoidable consequences include sudden health crises or natural disasters. These events cannot be foreseen or prevented, but resilience-building strategies—such as having an emergency fund, maintaining strong social support networks, or engaging in long-term health planning—help individuals cope when uncertainty becomes reality.

In these situations, resilience replaces risk mitigation as the primary strategy for dealing with uncertainty. While we cannot prepare for every unknowable event, we can develop adaptive systems that enable us to respond effectively when they occur.

Tying It All Together: Planning vs. Adapting

This framework helps specify when we can plan for outcomes and when we must be prepared to adapt.

Knowable and avoidable consequences belong in the realm of risk—they can be anticipated and proactively mitigated through planning and foresight.

Knowable and unavoidable consequences also fall under risk, and while we can’t prevent them, we can implement strategies to lessen their impact.

Unknowable and avoidable consequences introduce uncertainty, meaning we must be agile and flexible, adjusting our approach as new risks emerge.

Unknowable and unavoidable consequences exist in the realm of pure uncertainty—they cannot be predicted or avoided, making resilience and adaptability the best response.

Decision makers who conflate risk with uncertainty often struggle to make effective choices. Misinterpreting risk as uncertainty can lead to excessive caution or inaction, while treating uncertainty as risk can result in false confidence and miscalculated decisions. The key is knowing when to plan, when to pivot, and when to build resilience for the unknown.

By recognizing which category a given consequence falls into, we can tailor our decision-making strategies appropriately, reducing preventable risks, preparing for inevitable trade-offs, and maintaining flexibility in the face of the unpredictable.

One on risk vs. uncertainty and one on unintended consequences.

This is often a very subjectively derived estimate, sometimes being much higher or lower than would result from a more objective risk analysis.

Statistically, you actually have a higher probability of getting into an accident in the summer months, but given that 17% of all vehicle crashes occur during winter road conditions and 73% of accidents occur on wet pavement, it is difficult to dispute the conclusion that poorer weather conditions increase accident likelihood.

A recent health scare would fall into the category of newly-identified risks; having a car accident in the last couple of weeks would be an example of a recent bad experience, and having been in car accident where you were injured while driving in snow would be an example of a traumatic event.

It doesn’t necessarily mean we won’t choose that option. For example, it doesn’t mean we will never drive in the snow again, but it may mean we are more selective about when we choose to do so or allow others to drive when possible.

I don’t generally read articles focused on climate science or planetary systems. And I certainly don’t write about either of those topics, as both are outside my expertise. But Suckling et al. (2021)’s framework actually applies quite well to human decision making more generally.

At best, you can guess based on what you know about the destination’s typical weather for that time of year.

It was very enjoyable to read this clear distinction and delineation between risk and certainty, something I thought I had an intuitive sense of, but accept there's value in laying it down explicitly as Matt does in this article.

However, my joy was later tempered by the thought that if only our policy-makers applied these principles explicitly into decision-making since they affect many people in society!

But then I had to tell myself, our politicians are us, so it's better start by educating ourselves -- the public, the electorate, to understand and expect such an approach to be taken by our politicians. To that end, the ideas in this article deserve wide dissemination.

Thank you for this post, Matt. From a management perspective, risk and uncertainty are everywhere -- especially when you introduce change or are adapting to change. I think industries are getting better at managing it, but it can be subtle.

Your example with the self-driving cars was well-made. We can't know how risk will operate until we know how these vehicles will be used. But we have another example where new technology is already in use and the changing risk is not yet well perceived. For interest, here's a case-study.

In the US, the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) is a 3,000mi inland waterway along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts joining up inlets, saltwater rivers and canals to create an inland marine highway from Massachusetts via Florida to Texas. This waterway can be heavily trafficked by commercial and recreational craft; it needs to be periodically dredged and the deeper channels can shift over time which can be daunting for new captains of recreational boats, whose chart-reading and piloting skills may be weak, and who fear running aground.

For two decades it has been convenient to chart electronically not just ICW conditions but also a potential route along it, especially for nervous skippers. These 'tracks' can be used either manually or with autopilots to navigate and help skippers avoid running aground, so they function as a safety measure for captains with the weakest skills. There are both community-generated and commercial versions of such tracks.

But used collectively by skippers with a growing number of autopilots, such tracks also focus traffic in both directions along just one line. Being automatically calculated for ease of update, a track can also cut corners, directing traffic into oncoming lanes contrary to marine rules. So although when viewed individually it's a safety measure, when viewed from a systems perspective it could be a source of hidden and growing risk as more autopilots are used by captains who don't know better.

To rusted-on users, this looks paradoxical. How can a well-maintained and well-understood system that was safe to use in 2015, suddenly become less safe in 2025? But in fact, if you wanted to maximise the number of close encounters with weak skippers using popular navigation methods in congested waters, it would be hard to find more of them today than along these tracks. Yet even when the growing risk is pointed out, there's pushback: it's not dangerous until you *prove* it's dangerous. First show me the accident and *then* I'll believe the risk.

That's not really how we want to manage risk.